The Bank of England’s nine-member Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), led by Governor Andrew Bailey, meets next week to decide interest rates against a deteriorating external backdrop. By now, this should be a familiar picture for policymakers.

During the past five years, the Bank has been forced to steer the economy through three once-in-a-century shocks: a global pandemic, a major land war in Europe and now the worst policy-inflicted shock to global trade since the 1930s.

With some narrow exceptions, the US’s 145pc tariff on Chinese merchandise imports and China’s reciprocal 125pc tariff amounts to a de facto trade embargo between the world’s largest two economies.

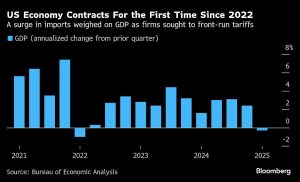

Even if the US and China strike a deal, significant damage to their own as well as the world economy has already been done. Judging by various warnings by US chief executives, including BlackRock’s Larry Fink, the US may already be in recession.

The reality is that no one really knows for sure what the coming year could entail for the global economy. And, of course, none of the standard models upon which central bankers base their decisions can capture the unpredictable nature of US trade policy under the Trump administration.

More than usual, the MPC will need to make a set of judgment calls to “promote the public good” – which is what the Bank’s 1694 charter sets out as its chief aim.

A 0.25 percentage point rate cut next Thursday to reduce the Bank Rate to 4.25pc is close to a done deal. But that would still keep the rate above the 2.8pc average since the bank became operationally independent in May 1997.

It would mark the fourth cut since policymakers started to ease the brakes in August 2024 and maintain the pattern of lowering rates at a pace of once per quarter at meetings when the bank publishes its Monetary Policy Report and the governor hosts a press conference.

So far, the Bank has kept rates unchanged at interim meetings – including at the last one in March.

The critical question for Thursday is not whether the Bank will cut, but whether it will have the courage to signal that it plans to accelerate future cuts as a precautionary measure against rising growth risks.

At the start of the year, economic logic argued for the Bank to stay in the slow lane. Growth momentum seemed to be picking up, and the UK had not fully gotten over the bitter inflation shock of 2022 and 2023.

And even though the Bank had expected inflation to return close to its 2pc target within two years, inflation looked likely to jump above 3pc for a period this year because of a temporary rise in energy prices. Plus, the combination of weak productivity growth and elevated wage pressures tilted inflation risks a little to the upside over the medium term.