(Bloomberg) — Emerging-market traders are shifting their attention to the path of the global economy and the US dollar after assets from across the developing world posted unexpected gains at the start of Trump’s administration.

Most Read from Bloomberg

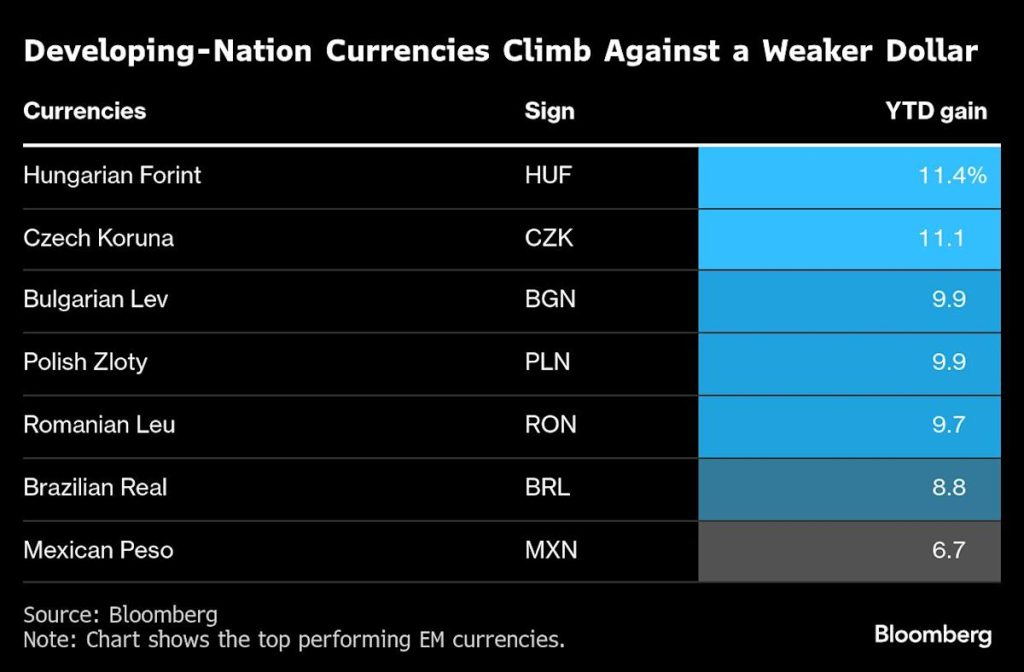

The tumult of Donald Trump’s first 100 days reverberated through financial markets, sending the greenback to a three-year low and hurting US stock and bond portfolios. Emerging markets, though, largely flourished with local currency bond returns jumping, a gauge of stocks handily beating the S&P 500 Index and a currency index clocking its best rally since 2017.

Now, as the dollar falters on fear the US is heading for a slowdown, investors say the outlook for developing-world assets hinges on just how much economic suffering Trump’s trade spat will cause.

Those questions dominated the halls of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank last week as government officials and investors met for the institutions’ spring meetings. The IMF cut its 2025 global growth forecast to 2.8% from the 3.3% it had projected in January, citing the potential fallout from Trump’s sweeping tariffs.

Foreign markets will benefit from a weaker US economy, said Luis Estrada, a strategist at RBC Capital Markets in Toronto, but there’s a fine balance.

“The sweet spot for EM is a US slowdown but not a recession,” he said on the sidelines of the meetings. “It’s certain that we’ll have a weaker dollar, and people are going to diversify away from dollar assets.”

A measure of developing-world stocks has returned 3.2% since Trump took office on Jan. 20, compared to a 7.5% loss in S&P 500 Index, with those in Latin America, South Africa and India rallying. Most EM currencies have gained since, compared to a 7% slump in the dollar.

“Emerging markets have proved lately that they can navigate a more challenging backdrop,” said Pierre-Yves Bareau, head of emerging-market debt at JPMorgan Asset Management in London, who favors local-currency bonds, which has climbed 3.5% this year, the best four-month start since 2019.

For some, the outperformance has brought hope that developing nations can pull back at least some of the $211 billion that investors have yanked out of the asset class since 2022, including about $30 billion this year.